We're Here, We're Queer, Get Used to It: A Lesson the Animal Rights Movement Could Learn

This fall, I've been listening in on a course I always intended to take as an undergraduate, U.S. Gay and Lesbian History by George Chauncey, and I've had to pinch myself for the last week or two as I read my way through Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities by John D'Emilio to remind myself that I'm not reading about the animal rights movement. The debate is so similar to, and the rhetoric so evocative of, the modern animal rights movement that it's impossible for someone in this movement to miss. So I've decided I should share some of the most interesting parallels in the book with a wider audience.

The book covers the early (pre-Stonewall) movement for gay and lesbian rights, particularly centering around the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis, two 1950s groups. The movement was known as the homophile movement in those decades. I don't think many of these examples are that biased by D'Emilio's own perspective, as the previous book we read, The Lavendar Scare by David K. Johnson, had a chapter on these groups that left me with a very similar sense and the same conclusions. Here are the parallels I see.

The overall parallel is this: the movement was divided between those who wanted to educate and integrate individuals and militant direct action for political change.

These terms (education, individuals, direct action, militant) are terms we frequently hear in discussion of animal rights strategy. I didn't take them from there - I took them from right out of the pages of D'Emilio's book.

1. A growing debate over whether activists should be likable and professional - and the less likable ones seem to have won.

In the animal rights movement, it's often said that we should appear as normal as possible, including wearing professional dress for protests. I don't want to dismiss this idea out of hand - there's little question that if I am trying to persuade someone one-on-one looking good and looking like them will probably help. I just want to note for now that the resemblance to the attitudes of the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis is striking. See, for instance, this excerpt from the Daughters of Bilitis' description:

Appearing normal was not simply a matter of dressing nice. It meant, all too often, accepting psychiatric theories of homosexuality as a mental disorder and welcoming religious figures who denounced homosexuality as a sin. I'm not making this up - the Mattachine Society at several points welcomed figures - psychiatrists and theologians - who would be considered hate-mongers today. This was a gay rights group, though, and it's important to realize that they undoubtedly laid the groundwork for the modern gay rights movement by creating a community of advocates for the first time that could then be tapped into by other groups.

Compare the DOB's self-description to this passage from the Vegan RD:

"We vegans eat (and live) in a way that is very different from the rest of the population. For some of us, it’s not a big deal. For those who value feeling normal, it might bring considerable discomfort regarding their vegan lifestyle. We can’t change the desire to be normal, but we can take steps to 'normalize' veganism."

Nick Cooney relays the story of an environmental organizer making big asks of activists to great admiration until he makes the biggest ask of all: cut your hair. The lesson is that, as activists, we must be willing to leave our identities at home in order to appear normal.

There is a difference between these two movements: as animal rights activists, it is our goal to have people accept animals, not us. But what is the same is that we face a tension between the social norms by which we live (and would like the world to live) and the social norms under which the world operates. We all want to be normal, and the common solution is to make ourselves normal. But in fact we can change the desire to be normal, at least some of us and at least briefly. That realization points another route forward - to force society to acclimate to our norms.

|

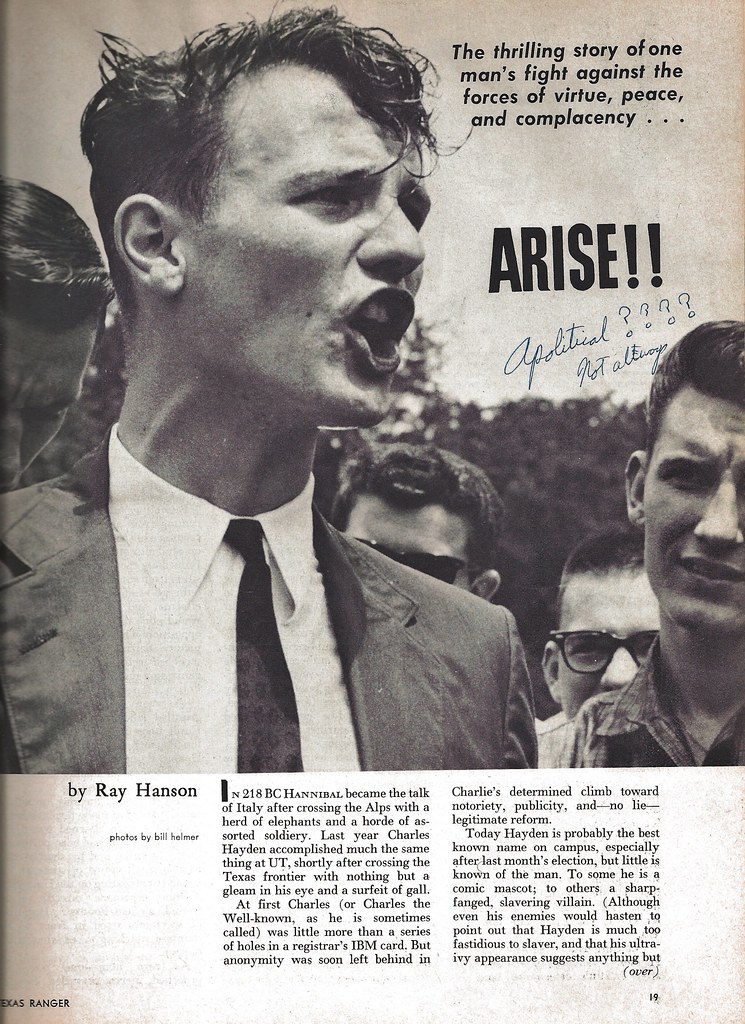

| Texas Ranger article about Randy Wicker |

In the gay rights movement, likability and professionalism came increasingly into question in the 1960s. In New York City, a man named Randy Wicker scandalized the Mattachine Society by taking public action and ultimately offering publications tours of the gay underworld, including bars and bathhouses, in an effort to capture publicity. Upon arriving in New York, he described:

"I couldn't understand why every homosexual did not actively support gay groups. . . . [Instead,] I was belittled. 'There's Miss Mattachine,' they would say. They didn't want to hear about it."

In Washington D.C., gay federal employees took to picketing outside the State Department which viciously persecuted gay men and women during the Cold War despite cautions from others that

|

| Picketing the White House in Washington, D.C. |

New York, Washington, and other cities where militants had a substantial presence were where things really began to take off - both in terms of generating public dialogue (major, and positive, press hits in Harper's, The New York Post, The Village Voice, and Playboy in New York and several prominent court cases and an alliance with the ACLU in Washington) and in terms of building up the activist network (previously stagnant numbers doubled in New York in the year after "The Wicker Basket" as it was called and soon quadrupled while Washington was similar).

There's such variation in strategies across cities in this period that I think we can draw some lessons, and the biggest lesson that cries out is that seemingly obnoxious activism worked. It got people's attention, both outside of the movement and within.

| Collectively Free, a grassroots animal rights network, protests outside Chik-fil-A |

In the excerpt from "What about the Daughters of Bilitis?" you can see repeated references to education. In fact, when Frank Kameny, now lionized as a hero in the gay rights movement, proposed taking on the government bureaucracy in Washington, D.C., which had led a crusade against homosexuals including extensive spying and invasive interrogations, the Mattachine Society's founders advised against it, saying we needed to focus on education first before pushing for change that was then seen as radical. Kameny pushed ahead and achieved the first legal win against a decades-long campaign of persecution and harassment of homosexuals by the federal government when a court ruled against the Civil Service Commission's firing of a homosexual government employee. The legal battles Kameny pursued also developed the support of the Washington chapter of the ACLU, which ultimately lobbied the national ACLU to overturn a 1957 ACLU statement in support of sodomy bans and federal security statues against homosexuals. It looks like in the most successful cities, the push came first, education second.

In the animal rights movement, to be fair, there are groups pushing for political change, such as bans on certain industrial practices. These do not generally have the grassroots component or the strong messaging that the campaign in Washington had. My sense is that it's common in the animal rights movement for us to feel that we need more people on our side before we can push for broader social change. In the 1950s and 60s homophile movement, it looks like a broad push was actually a critical first step before winning people over.

3. Numerous occasions in which backlash led to growth and public support.

| The response to a raid on San Francisco's Black Cat Bar |

This backlash dynamic has played out in the animal rights movement. Most notably, ag gag laws to ban recording in agricultural facilities have humiliated animal agriculture. In other examples, prosecutions of animal rights advocates routinely net public sympathy and increase the profile of the cause. It's not particularly novel to note that the backlash effect happens. What's remarkable is what a crucial role it seems to have played in the gay rights movement, particularly at key turning points.

Now obviously, as I've said, there's a key issue with the analogy, which is that with the early gay rights movement, it was largely the oppressed class - homosexuals - who were doing the activism, whereas with the animal rights movement, it's allies. But the parallels are so striking, not just in situation but in language, and the strategic considerations are extremely similar: how to transmit a message to U.S. society that is not yet accepted but that, at its core, reflects many individuals' fundamental values.

People often draw conclusions from history about current social movements, and they're often sloppy or gloss over serious issues. When drawing on history to try to infer causality and figure out best practices for a modern movement, it's important and extremely difficult to take account of all sorts of biases. Less memorable events, such as failed social movements, are less likely to show up in the historical record. With history, there's no counterfactual - you can't see the alternate universe where something didn't happen - and it is generally very hard to find a situation that is close to identical, which is the next best option. What's interesting in the pre-Stonewall gay rights movement is that you can see a great variety of tactics and strategies in different cities and with different timing, so I think you can get a better sense than with most cases of which strategies worked best. In this case, it seems pretty clear that the adoption of more confrontational political action led to greater success in public dialogue generated, pressure placed on institutions, and mobilization of activists.

As I was channel surfing the other day I saw a bit of Modern Family, including a quick scene of the delightful gay couple. I thought what incredible irony it is that the writer of that show, and of Will and Grace before it, will get little credit for having profoundly changed the world, whereas I am sure they deserve a big chunk of it. Those characters, on some of the most popular shows in history, made gay people likable, and made discrimination against them seem wrong to the average TV watching American. Likability matters.

ReplyDeleteTotally agree! I think Will and Grace ahve gotten a lot of credit, at least from people I talk to. (For example: http://variety.com/2015/tv/news/will-grace-gay-characters-lgbt-1201530893/) Randy Wicker, on the other hand, is unknown to most of America. All else equal, of course, you want to be likable, but I think there are other things that do too and sometimes outweigh it. Most of us don't have the visibility Will and Grace had, and I certainly don't think our movement does, so if we have to trade off some likability for more visibility it might be worth it.

DeleteZach: Considering the history, composition, leadership and, of course, my own experience at many conferences, forums and many other AR related happenings- over 15 years. I can't help but to understand "individuals ' in that sentence as "white individuals".Thoughts? Still, the parallels on many ways are remarkable.

ReplyDeleteYeah I think that's true. I think the Mattachine Society and the DOB were notably more white than the militant crowd.

Delete